Over the last several years, many analysts have argued that QE isn't inflationary because the money that the Fed has printed has been locked up in reserve balances. I don't personally share this view, but it's worth noting that recently reserve balances have been contracting and currency in circulation has been growing as banks have chosen to convert reserves to currency. Currency in circulation is now growing at nearly a 10% annual rate.

Pages

▼

Friday, November 30, 2012

QE3 Just Starting to Hit Fed Balance Sheet

Although QE3 was announced almost 2.5 months ago, the mortgages that the Fed has been purchasing have only just started to hit the Fed's balance sheet over the last couple of weeks. The monetary base has continued to hold flat, but mortgage holdings have ticked ever so slightly higher.

The Fed has agreed to purchase ~$100B worth of mortgages since September, but holdings have only increased by $40B due to the lag in time of settlement for MBS trades. The fact that the balance sheet has mostly been unchanged suggests that we may not yet have seen the effects of QE3 in securities markets.

Thursday, November 29, 2012

Nominal GDP Grew at 5.5% in 3Q12

The first revision of 3Q12 GDP was released this morning and showed that GDP grew at 2.7% annualized during the quarter, which was 0.7% better than the initial estimate. That's also 1.4% more than it grew in 2Q12, when it only grew by 1.3% annualized.

People often forget that the headline GDP number is reported on a "real" basis, which means that it is adjusted for inflation. In reality, real GDP is anything but real though, since the world is measured in nominal, not real numbers (especially important for debt), and economists do a debatable job of measuring inflation anyways.

On a nominal basis GDP was up 5.5% annualized last quarter, a pretty big number! The deflator (inflation) ran at 2.7% which is also a fairly large number in its own right. The 5.5% growth was actually the largest quarterly increase in nominal GDP this cycle, although it's not quite as large as it was at other points last decade.

People often forget that the headline GDP number is reported on a "real" basis, which means that it is adjusted for inflation. In reality, real GDP is anything but real though, since the world is measured in nominal, not real numbers (especially important for debt), and economists do a debatable job of measuring inflation anyways.

On a nominal basis GDP was up 5.5% annualized last quarter, a pretty big number! The deflator (inflation) ran at 2.7% which is also a fairly large number in its own right. The 5.5% growth was actually the largest quarterly increase in nominal GDP this cycle, although it's not quite as large as it was at other points last decade.

|

| Source: BEA |

Wednesday, November 28, 2012

Largest Powerball Jackpots in History

Tonight the lucky residents of 42 states (sadly not California) will get a shot at a $500m Powerball jackpot. Below is a chart of all the times that the jackpot has exceeded $200m. This has happened 28 times since 2002, about once every 134 days, or 2.7x per year. That isn't a whole lot different than the frequency of drawdowns on the S&P 500, which, like big jackpots, create favorable buying opportunities. Five percent drawdowns have happened about once every 163 days since March 2009.

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

Is [The] Santa Claus [Rally] Real?

The end of this week will bring the end of November, and with that there is the usual seasonal talk about a Santa Claus rally in the stock market. The logic goes that stocks usually rally between Thanksgiving and Christmas, but much like with Kris Kringle himself, it's fair to ask the question: does the Santa Claus rally really exist?

Looking at the historical data, since 1957 December has been a positive month on average for equities. In the past 5 years it has been especially good--powered by a nearly 11% gain in 2008 and 4% gain in 2010. Below is the average path that the S&P 500 takes during December. It demonstrates some Christmas magic may indeed exist--the path is even strangely sleigh like...

Looking at the historical data, since 1957 December has been a positive month on average for equities. In the past 5 years it has been especially good--powered by a nearly 11% gain in 2008 and 4% gain in 2010. Below is the average path that the S&P 500 takes during December. It demonstrates some Christmas magic may indeed exist--the path is even strangely sleigh like...

Monday, November 26, 2012

S&P 500 Down Just 0.21% In November

Even though we're set to open slightly lower this morning, the S&P 500 is hardly down at all for November. This is amazing considering that it was down as much as 5% mid month. The pattern is similar to 2011, when the S&P 500 was down by 7.5% mid month, but ended it down only 0.5%

Wednesday, November 21, 2012

Happy Thanksgiving to the 1% (That probably means you)

I'm re-posting this post from last year--I haven't changed a word. It's easy to forget that there was extreme bearishness then too, but after Thanksgiving 2011 we got a 5 month rally from ~1150 to ~1400. A similar rally this year would bring us to new all time highs.

Originally posted 11/23/11:

On a day that the Dow was down 236 points, it doesn't feel like there's much to be thankful for. Between Europe's collapse, Washington's gridlock and China's slowdown, it seems the world is a dangerous place for investors. Despite all the scary headlines, there is of course lots to be thankful for, even from an economic standpoint. Most notably: we are a nation of 1%-ers.

The Occupy Wall Street movement has drawn plenty of attention to the income distribution within the United States, pitting the 99% against the 1%. But what goes overlooked by these well meaning folks is that compared to the other 6.7B people on the planet, those occupying Wall Street probably don't come close to being in the 99%.

In the US it takes an income of $250,000 per year to be considered a 1%-er, but if you take the global population into the calculation, the number drops to just $47,500. Considering that median household income in the US is $50,000 per year, this means that at the very least half of Americans live in a household that earns at the 1% level. Even the US poverty line, which is set at a family of four earning less than $22,000 is not too far from being in the global top 10%.

Compared to inequity of global income distribution, the intra-US distribution is no great injustice at all. That is something to truly be thankful for.

Originally posted 11/23/11:

On a day that the Dow was down 236 points, it doesn't feel like there's much to be thankful for. Between Europe's collapse, Washington's gridlock and China's slowdown, it seems the world is a dangerous place for investors. Despite all the scary headlines, there is of course lots to be thankful for, even from an economic standpoint. Most notably: we are a nation of 1%-ers.

The Occupy Wall Street movement has drawn plenty of attention to the income distribution within the United States, pitting the 99% against the 1%. But what goes overlooked by these well meaning folks is that compared to the other 6.7B people on the planet, those occupying Wall Street probably don't come close to being in the 99%.

In the US it takes an income of $250,000 per year to be considered a 1%-er, but if you take the global population into the calculation, the number drops to just $47,500. Considering that median household income in the US is $50,000 per year, this means that at the very least half of Americans live in a household that earns at the 1% level. Even the US poverty line, which is set at a family of four earning less than $22,000 is not too far from being in the global top 10%.

Compared to inequity of global income distribution, the intra-US distribution is no great injustice at all. That is something to truly be thankful for.

Global Income Distribution

Data is from the World Bank.

Tuesday, November 20, 2012

HP's Horrible Acquisition Track Record

As I'm sure most are aware, HP announced today that it would be writing-off almost the entirety of its Autonomy acquisition, which was panned from the minute it was announced and resulted in Leo Apotheker's ousting.

In acquiring Autonomy, HP basically admitted that it set fire to about $9B. This would be bad enough if it wasn't for the fact that this is not the first, not the second, but the third time in a year that HP has admitted that a company it spent more than a billion dollars acquiring was worth far less than it paid for it. In 2008, HP bought Electronic Data Systems for $13.9B and wrote that down by $9.8B last quarter. In 2010 the company bought Palm for over $1B and shortly thereafter shut the operations down. In all the sum of these three write-downs is worth almost as much as HP's current market cap!

Worst of all, the carnage from the Mark Hurd/Leo Apotheker era still might not even be done yet. In 2010 (while the company was being led by an interim CEO if memory serves) HP made three other multi-billion dollar acquisitions at big revenue multiples. 3COM, 3PAR and Arcsight could each be a candidate for billion dollar write-downs as well.

In acquiring Autonomy, HP basically admitted that it set fire to about $9B. This would be bad enough if it wasn't for the fact that this is not the first, not the second, but the third time in a year that HP has admitted that a company it spent more than a billion dollars acquiring was worth far less than it paid for it. In 2008, HP bought Electronic Data Systems for $13.9B and wrote that down by $9.8B last quarter. In 2010 the company bought Palm for over $1B and shortly thereafter shut the operations down. In all the sum of these three write-downs is worth almost as much as HP's current market cap!

Worst of all, the carnage from the Mark Hurd/Leo Apotheker era still might not even be done yet. In 2010 (while the company was being led by an interim CEO if memory serves) HP made three other multi-billion dollar acquisitions at big revenue multiples. 3COM, 3PAR and Arcsight could each be a candidate for billion dollar write-downs as well.

Monday, November 19, 2012

What Happens if We Don't Go Over the Fiscal Cliff?

One thing that I think people aren't currently appreciating about the Fiscal Cliff is that congress is mostly debating how they plan to shrink the deficit, not really if they're going to shrink the deficit. So, whether there's a compromise or not, the US economy is going to be facing a similar picture in 2013: deficit reduction. (Of course, if we don't "go over the cliff" this deficit reduction might happen slower than in a compromise, and certainly a lack of compromise wont be good for market psychology, but from a technical spending point of view the outcomes are actually rather similar.)

In order to take a look at how the US economy has fared in past periods of deficit reduction, below is some important data linking GDP growth to deficit contraction. The chart shows the data for every year that there has been a contraction in the deficit as a percentage of GDP since 1929.

Over that time frame there have been 42 years that the government has spent less money relative to GDP than it did in the previous year, and the good news is that in the vast majority of those years, there has still been positive GDP growth. Real GDP only contracted in 7 of those years and Nominal GDP only contracted in 3 (two of which were in the depression). The reason that nominal GDP has fared better is that there is actually a strong history of inflation in years of deficit reduction--something to definitely watch for in 2013.

If the deficit shrinks by the full fiscal cliff amount of ~$500B next year, that would mean that the deficit would shrink by ~3% of GDP. Below is some data to put that into context relative to other years in which the deficit contracted by a large amount in a single year. Many of the data points are clustered around the post WWII period (when we ran our largest deficits captured by the data), but low real GDP growth and high inflation are characteristic of most of these years.

In order to take a look at how the US economy has fared in past periods of deficit reduction, below is some important data linking GDP growth to deficit contraction. The chart shows the data for every year that there has been a contraction in the deficit as a percentage of GDP since 1929.

Over that time frame there have been 42 years that the government has spent less money relative to GDP than it did in the previous year, and the good news is that in the vast majority of those years, there has still been positive GDP growth. Real GDP only contracted in 7 of those years and Nominal GDP only contracted in 3 (two of which were in the depression). The reason that nominal GDP has fared better is that there is actually a strong history of inflation in years of deficit reduction--something to definitely watch for in 2013.

|

| Source: Federal Reserve |

If the deficit shrinks by the full fiscal cliff amount of ~$500B next year, that would mean that the deficit would shrink by ~3% of GDP. Below is some data to put that into context relative to other years in which the deficit contracted by a large amount in a single year. Many of the data points are clustered around the post WWII period (when we ran our largest deficits captured by the data), but low real GDP growth and high inflation are characteristic of most of these years.

Friday, November 16, 2012

Federal Debt Compared to Household Net Worth

Much of the recent discussion about the fiscal cliff has focused on the role of the wealthy and their obligation to shoulder the public debt load. With the debt at $16T and the relative concentration of wealth in the US, the wealthy might not ultimately have much of a choice. The top quintile of wealth is going to have to shoulder almost all of the load.

America is a wealthy country, so technically there is enough money to extinguish the whole debt if we needed to, but it would likely take extending the scope of taxation beyond income and into wealth. The savings rate in the US ("leftover" income) is already very low, so there isn't a whole lot of room to tax income more without severely impacting consumption. There is, however, plenty of wealth, but it happens to be highly concentrated because low income households don't save much. The top 20% of households hold 85% of the country's net savings.

Below is a chart of what the richest Americans' wealth looks like in relation to the Federal debt. The Forbes 400 could only cover ~10% of the total. The top 1% could cover the whole amount, but it would require a one time tax of 71% of their net worth (which includes assets like real estate, which would be tricky to implement).

If Uncle Sam wanted to keep a hypothetical debt extinguishment tax to 30% of an individual household's net worth, it would have to extend the tax across the top 20% of households, which would include households with an average net worth of ~$700k (that works out to ~210k for that household).

|

| Source: Federal Reserve, Avondale Estimates of Net Worth Based on 2007 Wealth Concentration Statistics. |

Importantly this analysis only includes today's debt. It does not take into account the unfunded liabilities from social security and medicare. It's a little scary to think that the majority of American households have almost no savings and will be absolutely dependent on these programs as elderly. These two programs combined are estimated to have an NPV liability of ~$50T, which theoretically wipes out the net worth of the whole top 20%. Before anyone goes into crisis mode though, all that really means is that something will have to change over time.

Thursday, November 15, 2012

Employment and Competitiveness of Small Businesses

During the presidential campaign there was a lot of talk about the role of small business in employment. One of Romney's central theses was that the small business community is the largest creator of new jobs in the country and so we should give small businesses breaks to allow them to hire.

In actuality, small businesses may create new jobs but they aren't the largest employer in the country. Large companies with more than 500 employees employ slightly more than half of all working Americans, while firms with fewer than 100 employees collectively employ about ~30% of the workforce. Still, smaller firms are more labor intensive than large firms in that they spend a higher share of revenue on labor. Mid sized firms employing between 10-100 workers spend over 20% of revenues on their workforce. By contrast, large firms only spend 15%. (I'd guess the reason 1-4 employee firms looks relatively low is that the majority of income is proprietor's income rather than payroll).

Even though they employ fewer people, there are many more small businesses in terms of number of firms. However, since 1988 the average number of employees per firm has risen steadily (see below). This implies that there's been consolidation in the economy and the average size of US businesses is increasing. Today there are 5.7 million firms in the US, which is down 5% from the start of the recession. By category, the number of businesses with 20-99 employees shrank the most over this time frame, falling by 11% since 2007.

One might wonder if the business landscape has trended towards consolidation because of the labor intensity of smaller firms. Larger firms have the resources to spend on technology and globalization of supply chain, which improves efficiency and allows bigger companies to take share from smaller ones. One could probably argue in different directions as to the effect this has on the aggregate labor force, but the fact that large firms spend a smaller proportion of revenue on labor raises some underlying questions about the extent to which today's elevated unemployment is structural (vs. cyclical)--caused by the elimination of jobs through increased implementation of technology and business consolidation.

In actuality, small businesses may create new jobs but they aren't the largest employer in the country. Large companies with more than 500 employees employ slightly more than half of all working Americans, while firms with fewer than 100 employees collectively employ about ~30% of the workforce. Still, smaller firms are more labor intensive than large firms in that they spend a higher share of revenue on labor. Mid sized firms employing between 10-100 workers spend over 20% of revenues on their workforce. By contrast, large firms only spend 15%. (I'd guess the reason 1-4 employee firms looks relatively low is that the majority of income is proprietor's income rather than payroll).

|

| Source: Census Bureau |

Even though they employ fewer people, there are many more small businesses in terms of number of firms. However, since 1988 the average number of employees per firm has risen steadily (see below). This implies that there's been consolidation in the economy and the average size of US businesses is increasing. Today there are 5.7 million firms in the US, which is down 5% from the start of the recession. By category, the number of businesses with 20-99 employees shrank the most over this time frame, falling by 11% since 2007.

One might wonder if the business landscape has trended towards consolidation because of the labor intensity of smaller firms. Larger firms have the resources to spend on technology and globalization of supply chain, which improves efficiency and allows bigger companies to take share from smaller ones. One could probably argue in different directions as to the effect this has on the aggregate labor force, but the fact that large firms spend a smaller proportion of revenue on labor raises some underlying questions about the extent to which today's elevated unemployment is structural (vs. cyclical)--caused by the elimination of jobs through increased implementation of technology and business consolidation.

|

| Source: Census Bureau |

Katrina's Effect on Jobless Claims vs. Sandy

Before Sandy hit I mentioned that jobless claims would be one of the more sensitive economic indicators to any disruption caused by the storm. Checking back in, today we found out that jobless claims spiked 78,000 following the storm to 439,000. In 2005, claims rose by 96,000 after Katrina hit and it took six weeks for claims to fall back to their previous level.

Wednesday, November 14, 2012

S&P 500 Historical Annual Performance vs. Dow

After today's selloff, the S&P 500 is up 7.8% for the year (ex-dividends) while the Dow is only up 2.9%. This means that the S&P 500 is outperforming the Dow by 490 bps, which seems like a lot given that the indexes are both large cap indices.

Still if the indexes ended the year with this performance, it wouldn't be the largest historical spread between the two. In 55 years of S&P 500 history, there have been 10 years that it has beaten the Dow by more than 5% (ex-dividends). There are also 9 years that the Dow has beaten the S&P 500 by the same spread.

Makes you think--what's the point of benchmarking active managers if even similar benchmarks outperform one another from year to year?

Still if the indexes ended the year with this performance, it wouldn't be the largest historical spread between the two. In 55 years of S&P 500 history, there have been 10 years that it has beaten the Dow by more than 5% (ex-dividends). There are also 9 years that the Dow has beaten the S&P 500 by the same spread.

Makes you think--what's the point of benchmarking active managers if even similar benchmarks outperform one another from year to year?

Seasonality of Business Inventories

Business inventories were reported today up 0.7% for September which is slightly higher than expected. Inventories are an important economic data point to watch because GDP growth is highly sensitive to expansion and contraction in inventories. Currently, the inventory to sales ratio is at 1.28x which is slightly higher than it was to start the year. This is something to keep an eye on because if inventories rise faster than sales, there can be an inventory liquidation and a corresponding contraction in GDP.

Cyclically speaking, inventory data is important to GDP but is somewhat difficult to interpret because it is also affected by secular and seasonal variance. On a secular basis, businesses have found a way to continually become more efficient and reduce inventory over time. This makes it difficult to interpret what the "right" level of inventory/sales should be.

Seasonally, inventories will also shift in response to the holiday shopping season. The government data is supposed to be adjusted for this, but is imperfect. On average since 1992, inventories are ~6% higher in November than they are to start the year. This year, inventories have grown a little more than average since January. (Note that it's important not to read too much into whether that means that companies are "over-inventoried" because the chart is really just showing the seasonality in any single year.)

Cyclically speaking, inventory data is important to GDP but is somewhat difficult to interpret because it is also affected by secular and seasonal variance. On a secular basis, businesses have found a way to continually become more efficient and reduce inventory over time. This makes it difficult to interpret what the "right" level of inventory/sales should be.

Seasonally, inventories will also shift in response to the holiday shopping season. The government data is supposed to be adjusted for this, but is imperfect. On average since 1992, inventories are ~6% higher in November than they are to start the year. This year, inventories have grown a little more than average since January. (Note that it's important not to read too much into whether that means that companies are "over-inventoried" because the chart is really just showing the seasonality in any single year.)

Tuesday, November 13, 2012

5% Pullbacks Since the Start of The Bull Market

With the S&P 500 at 1384, we're currently more than 5% off of the most recent high for the S&P 500. This marks the 9th time since the market bottomed in March of 2009 that the S&P has had a draw-down of at least 5%.

Below is a list of all the times that the market has experienced at least a 5% pullback over the last ~4 years along with the duration of the pullback in terms of number of trading days to the bottom and number of trading days to the next peak.

The most recent pullback hit its lowest (closing) point 38 trading days into the draw-down, which is slightly longer than the average during this bull market (although the data is not exactly normally distributed).

Below is a list of all the times that the market has experienced at least a 5% pullback over the last ~4 years along with the duration of the pullback in terms of number of trading days to the bottom and number of trading days to the next peak.

The most recent pullback hit its lowest (closing) point 38 trading days into the draw-down, which is slightly longer than the average during this bull market (although the data is not exactly normally distributed).

|

| Note: expressed in trading days |

Monday, November 12, 2012

Have Top Performers Led the Recent Market Decline?

The S&P 500 is down a little over 5% since September 14th, and it feels like the decline has been led by some of the best performing stocks of the last few years. Apple is down 21.5% over that period, Chipotle down 25% and Monster Energy down 15%; these are just some examples of high fliers that have been hit hard over the last two months.

While it feels like there are a lot of high profile companies that have declined recently, in actuality the best performers since since 2009 have done slightly better than the market since September, while the worst performing stocks since '09 have continued to do poorly.

While it feels like there are a lot of high profile companies that have declined recently, in actuality the best performers since since 2009 have done slightly better than the market since September, while the worst performing stocks since '09 have continued to do poorly.

Thursday, November 8, 2012

Checking Back in on 2006 vs. 2012

Early this year (back on January 4th) I posted that 2009, 2010 and 2011 had followed the pace of the 2003, 2004, 2005 rally almost perfectly. Since then we've been checking back in periodically to see how well 2012 has paced 2006. The pattern has actually been eerily similar except for the fact that the pace of the rally that came off of the summer lows was slightly faster than in 2006 and reached a higher high. The recent 5% pullback has corrected for that though, and now 2012 looks almost exactly like 2006 again.

Wednesday, November 7, 2012

Are we Heading For a Recession?

Every time the equity markets go through a correction the recession chatter seems to pick up. In the last few days, the chart below has started to pop up around the internet in support of the idea that we might be heading for one again. It's a recession probability index (which isn't widely followed to my knowledge) but has a good track record of predicting previous recessions and is past the threshold that has signaled false alarms before.

The indicator was developed by two professors, Marcelle Chauvet and Jeremy Piger. The inputs are: "a dynamic-factor markov-switching model applied to four monthly coincident variables: non-farm payroll employment, the index of industrial production, real personal income excluding transfer payments, and real manufacturing and trade sales."

I'm not particularly familiar with this indicator so it's tough to know what the biases could be, but I generally tend to be somewhat skeptical of models like this one.

A more time tested recession indicator is the slope of the yield curve--when the spread between 2 year and 10 year treasuries is inverted recession normally follows. In a zero interest rate environment the yield curve may have lost some of its informational content, but it's been a great cyclical indicator for a long time and it's grounded in sound economic logic, so it shouldn't be totally ignored. Today, even though the curve has flattened since '09 it is still not at or near the zero threshold. As of right now I'm still on the lookout for the yield curve to go completely flat or invert when recession is imminent, even in this environment.

A more time tested recession indicator is the slope of the yield curve--when the spread between 2 year and 10 year treasuries is inverted recession normally follows. In a zero interest rate environment the yield curve may have lost some of its informational content, but it's been a great cyclical indicator for a long time and it's grounded in sound economic logic, so it shouldn't be totally ignored. Today, even though the curve has flattened since '09 it is still not at or near the zero threshold. As of right now I'm still on the lookout for the yield curve to go completely flat or invert when recession is imminent, even in this environment.

To clarify, I did write yesterday in my investor letter that I think recession will happen sometime in the next presidential term, but that doesn't necessarily mean it's imminent. My base case is that it could start sometime late next year absent a totally botched fiscal cliff. The forecast is mostly reliant on the average duration of economic expansions. As I've written before, this expansion would be short even compared to the 1933 expansion if it ended today.

What's Wrong With the Republican Party?

I happened to catch this interview last night on NBC which is definitely worth watching. Aside from the unfortunate phrasing "Latino problem" Mike Murphy strikes me as a pragmatic strategist who is correctly diagnosing the underlying problems for the Republican party. Last night's election proved that Republican party conservatism is anachronistic and will be need to be revamped before 2014 and 2016 if the party wants to remain relevant.

S&P 500 After Obama 2008 Election

Even though November 2008 was a much different market environment than November 2012, it's worth noting that equity markets sold off pretty hard after Obama was elected in 2008 too. The volatility surrounding the financial crisis was extreme, but leading up to the election the S&P 500 had found some footing rallying from 850 to 1000.

Following the election the S&P lost 25% in 13 trading days. On November 21 the S&P 500 made a near term bottom that would last until February 2009. There was a big intra-day reversal when it was leaked that Tim Geithner would be Treasury secretary. Four years later, as we wait to find out who his replacement will be, maybe that person could spark a rally of her/his own.

Tuesday, November 6, 2012

November 2012 Investor Letter

Below is a letter that is written monthly for the benefit of Avondale Asset Management's clients. It is reproduced here for informational purposes for the readers of this blog.

Dear Investors,

Tonight the presidential election will finally be over and the markets will have some certainty about who will be in charge of the US government for the next four years. The victor will celebrate, but I’m not sure that he should be so happy to have the job. Whoever is president, the next four years could bring some of the biggest challenges faced by an administration since Roosevelt.

The next president will have to make important decisions about the course of the public debt and deficits, which will determine the health of the American economy for decades to come. In dealing with these issues he will be forced to choose between inflicting short-term pain and risking long-term damage. Politically, neither is palatable, but real leadership requires the former. In his first term, Obama clearly chose the latter, but perhaps without the goal of re-election hanging over his head he can finally push for real change. On the other hand, if Romney is elected he will have to worry about a 2nd term and therefore may find it harder to think longer term than Obama can.

Unfortunately, either candidate will be confronted with these challenges before he’s even sworn into office. The fiscal cliff is rapidly approaching and a decision must be made about how to deal with it. If there isn’t a compromise, then recession is almost certain. If there is a short-term fix (which most expect) then maybe recession is avoided in the immediate term, but probably not for long. It’s highly likely that the next presidential term will face another recession anyways.

Statistically we should be on the lookout for one late next year, and to make matters worse, the next time recession hits, the president probably wont have the same stimulus tools at his disposal as he did in the last one. The odds are that $1T budget deficits and unlimited Quantitative Easing will be central to the cause of the next recession rather than a solution for it.

From a market perspective, next year is an eternity away though. For now, the only thing that most people care about is whether the market will go up or down on Wednesday. It’s easy to make the argument either way no matter who wins. Most market participants aren’t particularly fond of Obama, but they do love Bernanke’s QE policies, which are more likely to continue in an Obama presidency. Alternatively, while more investors would probably prefer Romney for the long term, in the near term uncertainty over QE would be extremely damaging to market sentiment.

Near term, most investors actually aren’t paying attention to a much more important force than the election: QE3 hasn’t technically hit the markets yet. The mortgages that the Fed has purchased take about 60 days to settle, so the first purchases made in mid September will begin to clear next week. Curiously, markets have gone down ever since QE3 was announced, and this is probably at least part of the explanation. We should start to see more of a boost from QE once the trades clear.

That leaves us still with lots of cash but looking to start reinvesting over the next few weeks. That cash served us well in October as markets declined, but I continue to expect the S&P 500 to get somewhere closer to 1450 by year-end. As I mentioned last month, cash becomes a less valuable commodity when the Fed prints more of it.

Scott Krisiloff, CFA

Dear Investors,

Tonight the presidential election will finally be over and the markets will have some certainty about who will be in charge of the US government for the next four years. The victor will celebrate, but I’m not sure that he should be so happy to have the job. Whoever is president, the next four years could bring some of the biggest challenges faced by an administration since Roosevelt.

The next president will have to make important decisions about the course of the public debt and deficits, which will determine the health of the American economy for decades to come. In dealing with these issues he will be forced to choose between inflicting short-term pain and risking long-term damage. Politically, neither is palatable, but real leadership requires the former. In his first term, Obama clearly chose the latter, but perhaps without the goal of re-election hanging over his head he can finally push for real change. On the other hand, if Romney is elected he will have to worry about a 2nd term and therefore may find it harder to think longer term than Obama can.

Unfortunately, either candidate will be confronted with these challenges before he’s even sworn into office. The fiscal cliff is rapidly approaching and a decision must be made about how to deal with it. If there isn’t a compromise, then recession is almost certain. If there is a short-term fix (which most expect) then maybe recession is avoided in the immediate term, but probably not for long. It’s highly likely that the next presidential term will face another recession anyways.

Statistically we should be on the lookout for one late next year, and to make matters worse, the next time recession hits, the president probably wont have the same stimulus tools at his disposal as he did in the last one. The odds are that $1T budget deficits and unlimited Quantitative Easing will be central to the cause of the next recession rather than a solution for it.

From a market perspective, next year is an eternity away though. For now, the only thing that most people care about is whether the market will go up or down on Wednesday. It’s easy to make the argument either way no matter who wins. Most market participants aren’t particularly fond of Obama, but they do love Bernanke’s QE policies, which are more likely to continue in an Obama presidency. Alternatively, while more investors would probably prefer Romney for the long term, in the near term uncertainty over QE would be extremely damaging to market sentiment.

Near term, most investors actually aren’t paying attention to a much more important force than the election: QE3 hasn’t technically hit the markets yet. The mortgages that the Fed has purchased take about 60 days to settle, so the first purchases made in mid September will begin to clear next week. Curiously, markets have gone down ever since QE3 was announced, and this is probably at least part of the explanation. We should start to see more of a boost from QE once the trades clear.

That leaves us still with lots of cash but looking to start reinvesting over the next few weeks. That cash served us well in October as markets declined, but I continue to expect the S&P 500 to get somewhere closer to 1450 by year-end. As I mentioned last month, cash becomes a less valuable commodity when the Fed prints more of it.

Scott Krisiloff, CFA

Opinions voiced in the letter should not be viewed as a recommendation of any specific investment. Past performance is not a guarantee or reliable indicator of future results. Investing is subject to risk including loss of principal. Investors should consider the suitability of any investment strategy within the context of their personal portfolio.

Monday, November 5, 2012

History of Party Control of US Congress

Apologies for back to back political posts, but it seems to be all that anyone is talking about until tomorrow is over.

Many political scientists argue that "realigning" elections happen in the US about once every 35 years. In these elections, there is a political paradigm shift and a redivision of the electorate along new party lines. Generally these realignments happen in conjunction with a major historical friction like the Civil War or the Great Depression.

In American history most agree that realigning elections happened in 1828 (Jackson), 1860 (Lincoln), 1896 (McKinley) and 1932 (Roosevelt). There's some dispute about whether one happened in 1968 with Nixon or 1980 with Reagan, although I tend to believe that we're still in a system representing the vestiges of the New Deal Coalition (1932).

Either way, it can be argued that the US political system is long overdue for a seismic fundamental shift. I think that growing interest in Libertarianism against the backdrop of high public debt and extreme monetary policy is indicative of a bubbling change in the electorate, but while these ideas have begun to influence the conversation (e.g. through the tea party and Ron Paul), we're not at a paradigm shift quite yet.

For some perspective, below is a chart showing the history of political party control of congress. The exact political epochs are debatable from historian to historian, but I based the labels in the graph loosely on the five party systems defined by wikipedia.

|

| Click to Enlarge. Third Parties and Independents Excluded. Data source: Office of the House Clerk |

Friday, November 2, 2012

S&P 500 November Return in an Election Year

After today, there are just two trading days until a presidential winner is decided (hopefully). The last time that an election felt as close as this one was in 2000 when Bush and Gore went head to head resulting in recounts, hanging chads and almost a month of uncertainty.

Although it's a long shot that we have a repeat of 2000 next Tuesday, there are plausible (although also low probability) scenarios in which an electoral college tie could happen. Especially given that the fiscal cliff is breathing down congress' neck, let's hope for everyone's sake that it doesn't happen. As a reminder though, below is what happened to the S&P for the month between the election and Gore's concession. Funny how the S&P 500 is basically starting at the exact same spot as it's at today.

Bush v. Gore was obviously a rare occurrence not expected to repeat, so below is a list of how the S&P 500 did in November in other election years since 1952. On average the S&P 500 is up in an election year in November, and slightly more when a one term President is ousted than when re-elected.

Bush v. Gore was obviously a rare occurrence not expected to repeat, so below is a list of how the S&P 500 did in November in other election years since 1952. On average the S&P 500 is up in an election year in November, and slightly more when a one term President is ousted than when re-elected.

Although it's a long shot that we have a repeat of 2000 next Tuesday, there are plausible (although also low probability) scenarios in which an electoral college tie could happen. Especially given that the fiscal cliff is breathing down congress' neck, let's hope for everyone's sake that it doesn't happen. As a reminder though, below is what happened to the S&P for the month between the election and Gore's concession. Funny how the S&P 500 is basically starting at the exact same spot as it's at today.

Bush v. Gore was obviously a rare occurrence not expected to repeat, so below is a list of how the S&P 500 did in November in other election years since 1952. On average the S&P 500 is up in an election year in November, and slightly more when a one term President is ousted than when re-elected.

Bush v. Gore was obviously a rare occurrence not expected to repeat, so below is a list of how the S&P 500 did in November in other election years since 1952. On average the S&P 500 is up in an election year in November, and slightly more when a one term President is ousted than when re-elected. |

| Note: Counted LBJ as one term President |

How Many Hours of Work Does it Take to Buy...

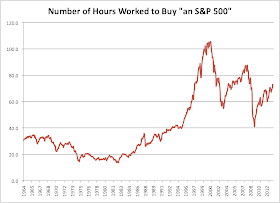

The reason that economists adjust nominal data to "real" numbers is that they are trying to create a better picture of general welfare after adjusting for inflation. If an economy produces $100 worth of widgets one year and $150 worth of widgets the next, the dollar increase doesn't tell you much if the price of a widget also rose from $100 to $150. In that case the economy has still produced one widget in the year, so welfare has not changed and theoretically real GDP should be flat.

At a fundamental level, "real" economic numbers are an attempt to measure output against time. In the previous example, the data was adjusted to have a more clear picture of the number of widgets produced per year. For humanity, time is really the only scarce resource there is. Therefore, the number of hours worked that it takes a person to buy an item is the true measure of welfare.

Today's employment report showed that average hourly earnings fell slightly to $23.58. Below are charts of the number of hours that it has taken to purchase a home, a barrel of oil, an ounce of gold and "an S&P 500," at the prevailing hourly wage of the era. In general a downward slope would mean that societal welfare is increasing because it would take fewer hours to buy the same good.

At a fundamental level, "real" economic numbers are an attempt to measure output against time. In the previous example, the data was adjusted to have a more clear picture of the number of widgets produced per year. For humanity, time is really the only scarce resource there is. Therefore, the number of hours worked that it takes a person to buy an item is the true measure of welfare.

Today's employment report showed that average hourly earnings fell slightly to $23.58. Below are charts of the number of hours that it has taken to purchase a home, a barrel of oil, an ounce of gold and "an S&P 500," at the prevailing hourly wage of the era. In general a downward slope would mean that societal welfare is increasing because it would take fewer hours to buy the same good.

Thursday, November 1, 2012

Financial Sector Volatility

Even though the S&P 500 was down by a little under 2% last month, and tech (as measured by XLK) was down 6.3%, financials (XLF) were up 1.8%. For beleaguered financial investors, it's been a long time since XLF didn't lead the market to the downside. The performance of XLF is hopefully an extremely positive sign for the markets and economy going forward. Even a $1B lawsuit against Bank of America couldn't bring the sector down in October.

Recently volatility in the sector has all but dried up. Below is a chart of the percent difference between the weekly high and low value of XLF going back to 2003. During the crisis this figure was as high as 45%, but last week it was only 1.9%.

Recently volatility in the sector has all but dried up. Below is a chart of the percent difference between the weekly high and low value of XLF going back to 2003. During the crisis this figure was as high as 45%, but last week it was only 1.9%.